The old capital of the great Purhépecha empire is located about 15 minutes from Pátzcuaro on the route described above.

The old capital of the great Purhépecha empire is located about 15 minutes from Pátzcuaro on the route described above.

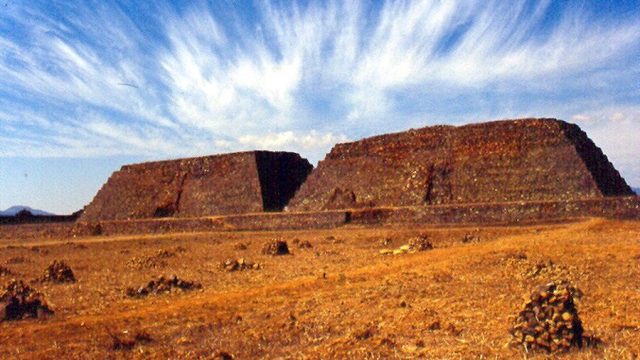

Its name means “humming bird place” and it is derived from the sound of the beating of hummingbird wings. This old city received tribute from 122 remote towns during the splendor of the imperial epoch, mounted an army of 250,000 warriors and figured as an important religious center which, it is presumed, was founded in the eleventh century. The Purhépechas formed a profoundly military and religious nation, believed firmly in life after death, and like the Egyptians, when an important person died, servants were killed and buried near their master to serve him in the next world.

In the same manner, prisoners taken in the battle had to choose between two options: slavery for life or a worthy death. For that purpose a sacrificial stone was used and can still be seen in the side of the main slope. The dead bodies were tossed down the hill and there remained until they disintegrated naturally.

Upon the arrival of the Spaniards the evangelization of the natives of the region began. It was very problematic to make room for so many people in the little Franciscan churches, and anyway the natives refused to enter. To facilitate the tasks of teaching the new religion and the baptism into the faith, creation of “open chapels” was resorted to, so-called because their altars opened onto large outdoor spaces, where large groups of spectators witnessed “sacramental acts” consisting of the re-enactment by priests of religious passages of the Bible, to facilitate learning by the natives.

These places also had baptismal fountains, in which the new Catholics were totally summerged. Right in Tzintzuntzan is the first open chapel in the Americas, and no written description can compare to a visit to see it. The crafts produced in this city include china and copies of prehispanic pottery of red clay, burnished or decorated with brush strokes in white; burnished china of smoked clay; glazed china decorated with regional motifs; green glazed china scratched and decorated with brushes; weavings of tule and chuspata into star-shaped mats, animal figures, baskets, lamps. And made of panikua there are Christmas decorations and traditional designs. Also it’s possible to find embroidered cotton blankets depicting ancient gods or Purhépecha motifs.

Another characteristic aspect of the old Purhépecha capital (and all the lacustrine region) is doubtless the celebration of the mystical, magical and awe-inspiring “Día de los Muertos”, Day of the Dead, which begins the night of the November first. The tradition says that during that night, the souls of those who have died return to visit the living.

Therefore homes and cemeteries are filled with candles, offerings, altars and delicious meals in honor of departed loved ones, saturating the atmosphere with tradition, veneration and nostalgia. During that night families go to the cemetery to pray and to remember anecdotes and stories of those no longer in the physical world. It has such impact on visitors that this heathen-religious celebration has become famous throughout the entire world; therefore if you wish to witness it, it is recommended that you make reservations well in advance. And when the day arrives, obey and respect all the customs and observe or participate respectfully in this ceremony.