Adress

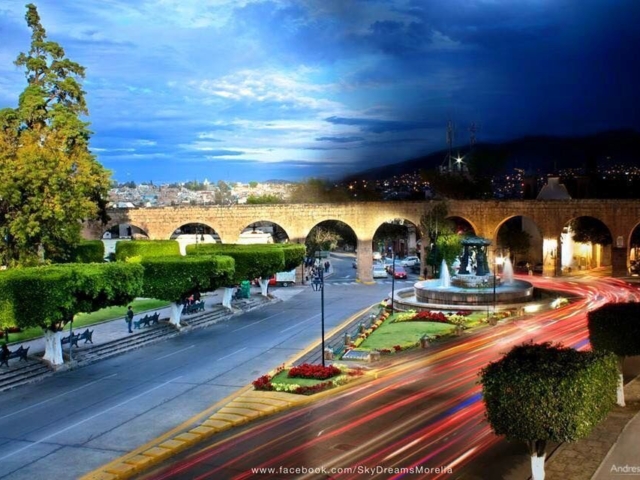

Av. Acueducto , 58260 Morelia, Michoacán, México.

GPS

19.69667286445, -101.16824626923

KNOW MORE PLACES

VISITA OTRAS LOCALIDADES

1.- Origins of the aqueduct.

With the taking of possession of the valley of Guayangareo, the distribution of lands for a plaza, cathedral, hospital, town hall and residents was carried out, and after the settlement of the first inhabitants of the area, the problem of water had to be solved. At first, it was an open-air canal that took advantage of the water sources near the valley, called the channel and the city's waterway, interchangeably. According to the city map of 1579, the water was supplied from some point in the Chico River.

In 1589, a tax on wine was levied for the construction of a new aqueduct. In 1598, the mestizo Cosme Toribio was hired by the Valladolid council to build a lime and stone pipeline that would lead to the main square of the city, where there would be a fountain for people to draw water. At some points, the primitive aqueduct was served by wooden channels. Throughout the 17th century, this system underwent several repairs and maintenance works.

2.- The 17th century.

According to the town council books, the aqueduct built at the end of the 16th century had to be repaired on several occasions, such as in the years 1615, 1643, 1657 and 1667. By 1677 the water supply became so difficult that the Viceroy himself donated 1,000 gold pesos to the city to help it.

The councillors of Valladolid asked the architect Pedro Nolasco to take charge of one more of the constructions to the water pipe. This new repair alleviated the problem of water supply to the city, as evidenced by a testimony from June 1678 by the notary Sebastián de Aragón, who certified the good condition of the irrigation ditch and water pipe, as well as the sufficient supply of the vital liquid.

The way in which the water supply to the city had been approached was not yet definitive, but, like the rest of the buildings in the very heart of the town, it was to undergo a radical transformation in the 18th century.

3.- The 18th century.

Manuel Escalante Colombres y Mendoza, bishop of Michoacán at the beginning of the century, ordered in 1705 that a stone archway be built to replace the pipe system inherited from the founding of the city. The old system was seen by the prelate as the origin of the intermittent water service and also of the gastrointestinal diseases that plagued the inhabitants of Valladolid. The monumental work of arches was finished between 1728 and 1730, and this gave way to the construction of its corresponding underground pipe, which within the perimeter of the city was to conduct the new flow of water. On March 29, 1731, the City Council agreed with the Alarife Nicolás Quijano, that he would take charge of the construction of the sewers and pipes necessary for the convenient distribution of water to the neighborhood and convents of the city.

On May 17, 1784, in a town council meeting, the alderman and provincial mayor reported that the day before he had been notified of the collapse of 30 yards of sewer and 22 arches, which was why there was no water supply in the city. More than a year later, on October 21, 1785, the work of rebuilding the city's aqueduct was given high priority, in which at least 53 arches were rebuilt and a new channel was made for the water, in addition to adding 4 water boxes, of which 2 remain.

The Bishop's charity work

Bishop Fray Antonio de San Miguel Iglesias, in order to better develop the work, bought from the Hacienda del Rincón the lands where the Carindapaz, El Moral, San Miguel and other springs were born. Mainly indigenous labor was used, since a large group of people in need were from this origin who had migrated to the city due to the drought. Between the years of 1785 and 1789 the work was carried out, which saved Valladolid from thirst and countless indigenous people from hunger.

4.- The 19th century.

Throughout this century the aqueduct continued to provide its services to the city of Valladolid, called Morelia from 1828, and also underwent some changes and repairs.

For example, in 1883 some works were carried out on the hydraulic system, including the height of the sewer. The water intakes in the archway were finished with battlements and gates. Two locks were cleaned and plastered. The sewer was covered to ensure the purity of the water and windows were placed section by section to facilitate cleaning. In 1886, 50 yards of the sewer were destroyed, and 522 pesos were spent to repair the fault, which prevented the normal flow of water.

The lost arches

Very notably, between 1896 and 1897, the 12th and 20th arches that ran from the current junction of the Acueducto and Tata Vasco avenues to the San Diego convent, to the north, were demolished. A piece of this arch still exists, which can be seen on both sides of the aqueduct, especially from Tata Vasco Avenue looking at the north face of the aqueduct. The stones from these arches were used to build public laundries, as reported in the Porfirian newspaper La Libertad.

As part of the hygienist movement that permeated positivist governments throughout the 19th century, such as that of Porfirio Díaz, a way was sought to guarantee the water supply to the city through healthier means, and it was at the beginning of the 20th century that projects began to be created to replace the classic aqueduct with another system.

5.- The 20th century.

The American engineer John Lee Stark, who in 1903 had proposed a system of filters to purify the water, whose system was inaugurated in 1906 with disastrous results, caused great problems for the administration of the Porfirian governor Aristeo Mercado, and even the official media deplored the erratic operation of the very expensive water treatment plant.

The American engineer John Lee Stark, who in 1903 had proposed a system of filters to purify the water, whose system was inaugurated in 1906 with disastrous results, caused great problems for the administration of the Porfirian governor Aristeo Mercado, and even the official media deplored the erratic operation of the very expensive water treatment plant.

In 1910, the brand new work, which is now known as the Filtros Viejos, was inaugurated and the already bicentennial quarry aqueduct went from being a public good to becoming the largest monument (over 1,600 metres long) in the city. Of the 30 fountains that it fed at its peak in the 18th and 19th centuries, some still remain, also as ornaments in the garden of New Spain.